Gradient Descent in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) (part 1)

Motivation #

I’ll admit it: I don’t know what a neural network is. I have gotten by \(n\) years of my life successfully without picking up more than a precursory knowledge of it. It’s made up of neurons, weights, and biases, but I’m not really sure what any of those things mean or how they correlate.

What I do have, though, is a couple of analysis classes under my belt. So when I hear machine-learning types talk fancy about “gradient descent” my ears perk up. I know what that’s about! Since I was never really able to wrap my mind around how training a neural network works (though 3b1b has some great videos on it), I thought that perhaps we may look at one of the most fundamental steps of it from a purely analytic perspective. We may be able to gain some good intuition about how neural networks work by considering the mathematical objects that represent them.

I will attempt to keep this post approachable for a student who’s taken a high school level calculus class. If you’re math-averse, this might not be the post for you, presuming you haven’t left already.

Who’s a gradient? #

If our goal is to understand gradient descent, it would do us some good to understand what we mean by “gradient”. And to understand “gradient”, we want to start by understanding linear approximations.

Say we had a smooth function on the real numbers \(f(x) : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\), where “smooth” means that we are free to take as many derivatives as we want. Suppose this function was really hard to calculate. However if we were given a tangent line \(x \mapsto ax+b : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) that was tangent to \(f(x)\) at \(x = x_0\), then it would be very easy to calculate an estimate to the value of \(f(x)\) very close to the point \(x_0\).

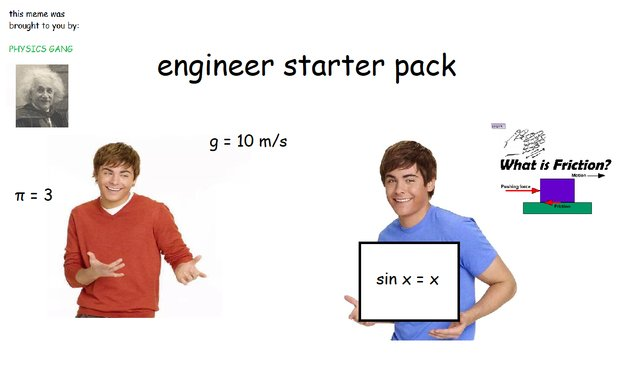

Here’s a concrete example of this: the memes about engineers who like to approximate \(\sin(x)\) with \(x\).

At \(x = 0\), \(\sin(x)\) starts to look a lot like \(x\). Don’t believe me? Below, I’ve plotted \(x\) and \(\sin(x)\) right next to each other. Do me a favor and zoom in as far as you can to the origin \((0,0)\). Eventually you’ll reach a point where the two plots coincide. On a small enough scale they look identical! In fact, on my screen, the two lines are identical after only zooming in for a few moments to the x-bounds \((-0.2, 0.2)\).

For someone not well versed in linear approximations, this behavior might be surprising. “So every function looks like a straight line when you zoom in?” you might now ask. Well, I’m happy to tell you that you and your engineer buddies would be correct*!

(*sort of)

Analytic, shmanalytic #

Let us be a little more precise. There is a class of functions known as analytic functions which have two special properties. First, they have “smoothness” like we established above. You can take infinite derivatives of an analytic function. Second, they are representable as a polynomial of the form

\[f(x) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty a_n(x-x_0)^n = a_0 + a_1(x-x_0) + a_2(x-x_0)^2 + a_3(x-x_0)^3 + \dots\]

where \(x_0\) is the “center” of our polynomial. This might look vaguely familiar to you: it looks like a Taylor series! While further discussion about analytic functions would not be relevant to this post, it is interesting to note that the class of analytic functions is exactly the class of functions you can write “well behaved” Taylor series for, on every point \(x_0 \in \mathbb{R}\).

Most functions you deal with on a day-to-day basis are analytic – polynomials, exponentials, and trigonometric functions. Here’s a function you might have seen that is explicitly non-analytic:

That’s right, the absolute value function \(|x|\) is a perfect example of a non-analytic function. Try zooming into the origin, right where the function makes a hard cusp. You can zoom in all you want but you will never hit a level where you could reasonably place a tangent line to make a linear approximation of \(|x|\) at the origin.

Non-smooth functions like \(|x|\) are obvious, non-pathological examples of non-analytic functions. However, this is not the only condition there is to break. There are many examples of smooth functions which are nonetheless non-analytic. I find most of them quite pathological so I don’t want to present them here, but if you are interested then Wikipedia does a fantastic and thorough job looking at a couple. Pay special attention to the first function listed with \(e^{-1/x}\), it’s one of my favorite examples in real analysis and it pains me to cut this section short and not talk about it.

Let’s get back on track: why do we care about analytic functions? I’ve introduced them for the sole reason that they’re really nice to work with. Most, if not all, functions can be roughly approximated by analytic functions using Fourier series and transformations of that nature. The bottom line is that only considering analytic functions makes our lives a lot easier and facilitates an easy transition when we go from talking about functions to talking about neural networks.

Operator magic #

It should come as no surprise that the gradient has something to do with linear approximations. Let’s go out on a limb then and define the gradient as an operator which takes an analytic function and gives you back the all information you need to construct a linear approximation. Let’s call it \(\nabla\). In mathematical language, we have: \[\nabla : C(\mathbb{R}) \to \text{???} \] \[\nabla(f(x)) = \text{???} \]

where \(C(\mathbb{R})\) is the set of analytic functions in the reals \(\mathbb{R}\). Note that I have replaced everything that we don’t know yet with the placeholder \(\text{???}\). We don’t know exactly how the gradient operator outputs yet, and we don’t know exactly what space that output is going to be in.

We now ask ourselves: what do we know? We know that \(\nabla\) gives us the “information” to construct a linear approximation. Let’s see exactly what information we actually need by constructing a linear approximation! Consider the function \(f(x) = sin(x)e^{x}\), a real ugly (but analytic) function on \(\mathbb{R}\):

We want to construct a linear approximation around the value \(x = x_0\), so we need a way to construct a line centered on a certain point. The point-slope form comes in clutch here. If we want a line passing through passing through our function \(f(x)\) at \(x = x_0\); then we really want a line that passes through the point \(x_0, f(x_0)\). So, we plug everything we have into point slope form in order to construct our linear approximation!

Great, now we have our linear approx—

Wait a moment. \(m\), the slope of our linear approximation, doesn’t have a definition! That is the sole piece of information we need to finish constructing our line! Recall that our informal definition of \(\nabla\) was that it gives us “all the information [we] need to construct a linear approximation”. And if \(m\) is the only bit of information we need, then it must be the case that \(\nabla(f(x)) = m\). This gives us the new linear approximation:

From this formula, we may actually finish our definition of \(\nabla\). Note that \(y(x)\) exists in the same space that \(f(x)\) does, which means \(y(x) : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) holds. Just looking at the terms of \(y(x)\) we can see that \(\nabla(f(x))(x-x_0)\) must exist in \(\mathbb{R}\), and that we have some real valued term \((x-x_0)\) being multiplied by something called \(\nabla(f(x))\) in order to get a real number. It would not be a wild guess to say that \(\nabla(f(x))\) is real valued. What other construct do we know that gives us a real value representing the slope of a curve at a specific point?

That’s right: the gradient is the derivative.

Let’s now go ahead and construct the concrete linear approximation. Let’s say that we want to approximate our function around \(x_0 = 1\), though we could choose any value because we’ve left \(x_0\) unbound until now. Recall that we defined \(f(x) = \sin(x)e^x\) earlier. We can take the derivative using the product rule: \(f’(x) = \sin(x)e^x + \cos(x)e^x\). From there, we simply plug into our formula for the linear approximation:

Let’s plot it to make sure we’re right!

Looks good to me! Zoom into the graph at \(x = 1\) and notice that at some point our approximation is indistinguishable from the original curve.

A little less magic #

There is one final problem to rectify, and it’s one with the notation that we’ve invented. We constructed \(\nabla(f(x))\) in a magical sort of way such that it is happy to give back the correct value of \(m\) regardless of what value we pick for \(x_0\). This is impossible! Math equations have no knowledge of the “context” they’re living in, so unless we redefine \(\nabla(f(x))\) for every problem we do, it’s sort of useless as it is. We rectify this by allowing \(\nabla(f(x))\) to simply give back the derivative of \(f(x)\), and as such we now have the following equality:

We can now give a real, solid definition for the definition of \(\nabla\) specialized to analytic functions on \(\mathbb{R}\): \[\nabla : C(\mathbb{R}) \to C(\mathbb{R}) \] \[\nabla(f(x))[x_0] = \frac{\text{d}f}{\text{d}x}[x_0] = f’(x_0) \]

So the gradient operation maps functions to their derivatives.

More formality #

Until now, we have been referring to the function \(f\) by it’s full qualified name \(f(x)\). It’s not really necessary to mention what variable \(f\) deals with though, so mathematicians tend to write an application of this operator as \(\nabla f\). This is much more than just a notational curiosity. \(\nabla f\) represents that there is a fundamental action happening to \(f\), which is what we’re trying to capture. This action produces another function, which we can then pass a variable to and get a different output. This is captured in the type of \(\nabla\), being \(C(\mathbb{R}) \to C(\mathbb{R})\). We tend to drop the parens around \(\nabla f\) as well since it is obvious what is happening. Therefore note that the following notations are equivalent: \[\nabla(f(x))[x_0] = (\nabla f)[x_0] = \nabla f(x_0)\]

Full speed descending #

Congratulations! We now know everything we need to know about the gradient for now, sans one piece: the gradient is really helpful at showing us which way is down.

Why do we need to know which way is down? It’s an important thing to know sometimes! Our function \(f(x) = \sin(x)e^x\) is rather simple and detached to the real world, but \(f(x)\) could theoretically represent anything. It could be the net profit made where \(x\) is the amount of people you hire! In that case, you’d really want to find the value of \(x\) which maximizes your profit. Therefore, you’d want to find the value which minimizes your net losses \(-f(x)\). This is what I mean by “knowing which way is down”: we want to know which direction we can travel on our function in order to minimize it.

Take another look the approximation we constructed previously. Only considering our approximation and the single point that it touches our function, how do you think that we could tell which direction causes the value to go down?

Think about the following situation: what if \(f(x)\) was really hard to compute? What if it was impossible to compute? What if all we really had to go off was the linear approximation at \(x\)? I am going to appeal to ethos for a moment and claim that the linear approximation is all we need to be able to minimize \(f(x)\).

“So,” you ask, “how can you tell?” The answer lies within a property of the gradient. As it turns out, \(\nabla f(x)\) always points in the direction of steepest increase. This makes little sense to claim for the real numbers, but once we expand past the real numbers it’ll be clearer why this is needed.

In our graph above, we see that our gradient takes a value roughly equal to \(3.75605\) at \(x = 1\) (this is the slope of our line). Based on my claim, that would mean that somehow the value \(3.75605\) “points in the direction of steepest increase”. And that it does! The value \(3.75605\) really tells us “at \(x = 1\), it is the case that \(f(x)\) is growing \(3.75605\) times faster than \(x\)”. Most importantly, this value is directional. It implicitly relies on the assumption that when we say “\(f(x)\) is growing” we really mean “\(f(x)\) increases as \(x\)” increases.

We may now ask the question “well, what does \(f(x)\) do when \(x\) decreases?” Though it seems silly, it is well formed! Let’s ask the differential what happens (thank you Lebiniz for allowing us to manipulate the \(\text{d}\)): \[\frac{\text{d}f}{\text{d}(-x)} = \frac{\text{d}f}{-\text{d}x} = -\frac{\text{d}f}{\text{d}x}\]

From this, we may derive the well formed statement “at \(x = 1\), it is the case that \(f(x)\) is growing \(-3.75605\) times faster than \(-x\)”. We see that it is the sign of the value that actually tells us the information we were after! As it turns out, the sign of \(\nabla f(x)\) gives us exactly the direction we should go to decrease the function:

for some value \(\varepsilon \in \mathbb{R}^+ \setminus \left\{0\right\} \).

Note that \(\varepsilon\) is added to the argument of \(f\) if \(\nabla f(x)\) is negative, and that \(\varepsilon\) is subtracted from the argument of \(f\) if \(\nabla f(x)\) is positive. This clues us in that we might not have to have two separate cases for moving left and right! We are in fact able to combine these into one case that minimizes \(f\) regardless of whether it is increasing or decreasing by simply relying on the sign of \(\nabla f(x)\). So we now have:

for some value \(\varepsilon \in \mathbb{R}^+ \setminus \left\{0\right\} \).

Take a step back for a moment and notice what we’ve just shown. I realize we got pretty deep in the weeds but the conclusion is quite clear. Spend some time allowing the next sentence to sink in. For any real analytic function \(f\), there exists some positive real number \(\varepsilon > 0 \), which is probably incredibly tiny, which satisfies \(f \left(x - \frac{\nabla f(x)}{|\nabla f(x)|}\varepsilon\right) < f(x)\) as long as \(\nabla f(x)\) doesn’t equal \(0\) at whatever value of \(x\) we’re working with.

This is such an important result because it allows us an alternate characterization of \(\nabla f(x)\): it is the unique function that takes in a point \(x\) and gives you back something which always points in a direction that increases \(f\) with a magnitude equal to the slope of \(f\) at \(x\)! We showed that the point you get back always points in an increasing direction in this section, and we showed that its magnitude is equal to the slope in the section “Operator magic”. Keen readers may then notice that I used some verbage in this paragraph that I haven’t used before, namely that whatever comes out of \(\nabla f(x)\) has a “direction” and “magnitude”. Ponder!

Multi-track drifting #

In the next part of this blog post, we will expand the definition of \(\nabla\) to multiple dimensions. From there we will finally see how this all relates back to the neural network! We’ve studied a lot of novel concepts here so I will leave you with a question to ponder. Say you had a neural network with two neurons – one input, one output. Then, let \(x \in \mathbb{R} \) be the value you feed into your input neuron, and let \(g\) be an analytic function in the reals such that \(g(x)\) is the value you get back from your output neuron. We represent our function \(g(x)\) by \(g(x) = L(a(x)) + c\) where \(L : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) is an unbounded monotonic analytic function you cannot change, \(a : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\) is a linear function given by \(a(x) = mx+b\), and \(m,b,c \in \mathbb{R}\) are arbitrary parameters you may tweak.

Using the gradient, can you minimize the expression \(g(x) - x\)?