A Basis For Sequential Execution: Monads, Arrows, and More

On the first day, there was light.

On the second day, there was silicon.

And on the third (?) day, there was assembly.

Screens were overfilled with the grace of bytecode shorthand. Three letter opcodes were all the information that A Real Programmer would need. jmp, cmp, mul, add. Each translated byte would become an elegant haiku of the code being run. The entire world surrounding the code could have been described over a quick coffee at the watercooler.

Then, computers got bigger. They got faster, they got more complex. There became too much for a single programmer to consider. Even a fleet of the world’s best programmers couldn’t write a triple A game in x86-64 assembly. Banks didn’t like watching nerds with glasses twiddle their bits all day long.

So, the humble computer language came to be. First COBOL, then C, then Javapythonrubyc++phpjavascriptvba.

But mostly, C. C is, was, and will always be, a beautiful language to run on a PDP 11. But as C became more widely (ab)used, it became increasingly apparent that C could be just as hard to reason with as the bit-twiddling lingua franca of yesteryear.

static float CURSED_VALUE = 1.0f;

volatile const char* possibly_incorrect_format = "%d\n";

void effectual_func() {

curse_of_the_elders:

printf(possibly_incorrect_format, CURSED_VALUE);

goto end;

}

int main() {

goto curse_of_the_elders;

end:

return 0;

}

“But Tyler”, you may ask. “Who would ever, in their right mind, write code like that?”

If you had the forethought to ask that question, you’re probably an above average programmer. And that implies the existence of below average programmers who would happily write that code and go along with their day, unbeknownst to the eldritch horrors they’ve summoned as that tangled spaghetti web of code becomes slathered across multiple files and compilation units.

So, a few people came along and made programming make more sense. They birthed forth type systems and side effect management. They covered up the computer’s inelegant internals just as rust may cover a metal. They made it possible to check if your code was safe before even letting it near an execution environment. They brought the best bits of math and computing closer than they’d ever been.

But, before we dive into all this, we must answer a question: what does it mean to run code?

There is a suprising amount of theory behind what it means to compute, to run code. There are plenty of different models of computing that one can use, such as the finite state machine, but by far the most common one is the Turing machine..

Since this isn’t really required theory for the rest of this post, we don’t have to get into the mathematical weeds about what exactly a turing machine is. It will still be good to internalize it as we move forward, though. If this piques your curiosity, a link is provided above.

The gist is that a Turing machine is a hypothetical computing machine that has a “state register”, a “state transition function”, a “head”, and a “tape”.

The state of the machine is determined by its state transition function. The state transition function depends on what symbol is currently being read off of the tape, and has the ability to modify the state of the machine by moving the head, writing a symbol to the tape, or changing the state register.

This seems exceedingly arbitrary, but think of it this way: your computer can do only a very limited number of things. It reads a program from memory, and depending on how it interprets the instruction it is currently reading, it can:

- Modify the tape (read/write a value from memory)

- Move the head (modify the

PC/IP) - Or, modify the state register (read/write a value from a CPU register)

The complexity comes from how we can combine these things. And, by God, it can get complex. So that’s why it’s incredibly useful to have some abstractions over this very raw theoretical model.

Now, we are finally ready to talk about “sequential execution”. Sequential execution is exactly what it sounds like: executing one thing, then executing another. On a computer, this can be extremely messy, as there is no way to know how executing an arbitrary piece of code can effect the overall state of the computer.

However, in mathematics, we have the concept of…

Pure Functions #

… which allow us to be able to represent the sequential execution of two pieces of code \(f\) and \(g\) as nothing more than \(f(g(x))\) for some input \(x\).

A pure function is a function which does not modify state in any measurable way. I make the distiction of saying “measurable”, because anything that you do on a computer will affect the state of said computer. adding numbers requires you to overwrite a CPU register, for example. But most programming languages allow you to abstract over these minute state modifications since the compiler is smart enough to handle them itself.

Let’s consider the composition of two C functions: \(f\) will add three to our input, and \(g\) will take the square root of our input. This will be the last C that we’ll write, so enjoy it while it lasts.

#include <math.h>

float f(float x) {

return x + 3.0;

}

float g(float x) {

return sqrt(x);

}

Then, the composition of these two functions is represented as f(g(x)), such that x is a float which gets square root-ed, then gets 3.0 added to it.

Let’s take this very simple example to introduce Haskell – representing the future bases of sequential execution will be much, much easier if we use a language that’s aware of how it executes things.

We’ll define our same functions here, but this time in Haskell.

f x = x + 3.0

g x = sqrt x

(If you’re already a Haskeller coming into this blog post, you most definitely won’t enjoy the nonstandard formatting that I plan to use. I am doing this simply because I’m using Haskell as a vehicle to explain these ideas, not as a tool in and of itself.)

Now that we have these functions, we can make an observation. \(f(g(x))\) is the same as applying the composition of \(f\) and \(g\) to \(x\): \((f \circ g)(x)\).

Haskell understands this, and allows us to say exactly that. The sequential composition of f and g is (f . g)(x).

Not every bit of code is as simple and self-contained as our hypothetical \(f\)s and \(g\)s. In order to get to the heart of execution, we need to be able to represent code that does something. Haskell’s type system enforces functional purity, so those functions f and g above cannot do anything outside of simply returning their modified arguments else the compiler will reject them. We’ll look at how Haskell chooses to deal with this criteria, but first, we’ll look at the down and dirty method of handling program state.

Continuations #

Continutations are the bread and butter of control flow in Scheme and other similar Lisps. Unfortunately, I pronounce my fricatives quite clearly (ba dum tss…), so I can’t really give code examples for using continuations.

The idea behind continuations, though, is treating the computer’s state as a first class object. Then, using primitives such as call-with-current-continuation, the programmer can force other blocks of code into using certain continuations despite their written context. As far as methods for handling composition and sequential execution, using continuations directly is rather dirty because it requires manually juggling the state across every function called under continuations.

I may not speak Lisp-y, but I can read Lisp – and Lisp code that overuses continuation passing is nearly as unreadable as the C example given at the top of the page. The best of the worst is still by no means good.

At the end of the day, though, continuations are quick and dirty but they work. Along with a conditional function, continuations give the programmer the power to derive every other bit of control flow.

Because of the arbitrary jumping and context passing, continuations are very hard to represent under a strict type system. They’re nigh impossible to represent in Haskell without a dedicated Continuation type, as there’s no state to access from Haskell’s pure-by-default functions anyway. To look at how Haskell gets around this, we must look at…

Monads #

Monads are the Haskell programmer’s calling card. Monads are also the reason why every failed attempt to learn Haskell eventually meets its doom. It’s simple – “monads are just monoids in the category of endofunctors”.

All jokes aside though, monads are not super complicated to understand. They’re one way to abstract over this idea of composition. In essence, they give you the ability to change what it means to write \(\circ\) and \((x)\) in \((f \circ g)(x)\).

In Haskell, being a monad means a couple important things for us. First off, monads contain values, but they can also contain state.

It also means that we have a monadic way to sequence functions,

(>>) :: (Monad m) => forall a b. m a -> m b -> m b

(Anyone who’s taken a proofs class will at least be somewhat familiar with that syntax – it says that for any Monad m, and for any two types a and b, the (>>) operator takes an m containing a and an m containing b and gives back an m containing b unchanged).

But, you may ask, why in the world is (>>) useful if it just gives back an m containing b unchanged? The secret is in the state. At a very high level, this state is stored in the m, and not in the b. So, (>>) allows us to “carry state” through the computation.

To see an example of this, let’s consider the IO monad, which abstracts over the real world state of your machine. Let’s define a few functions that just print to the terminal.

f = putStr "hello "

g = putStr "world"

These functions both have type IO (), meaning they monadically manipulate some IO state yet give back no value. Running f alone prints hello to the terminal, and running g alone prints world to the terminal.

Let’s compose these two functions.

Our composition (f >> g) still gives back nothing, but we now modify the state abstracted by IO twice – first by f, then by g. So, running (f >> g) prints hello world to the terminal. Sweet!

We’ve abstracted over \(\circ\), but we’ve yet to abstract over how to apply a value to these monadic actions. This is the \((x)\) we mentioned earlier. This “binding” of a value to a function comes in the form of the “monadic bind” operator in Haskell:

(>>=) :: (Monad m) => forall a b. m a -> (a -> m b) -> m b

This should be read similar to the last type that was presented. Given an m a and a function that brings you from a to m b, you can create an m b.

Now, we have everything that we need to create what’s called do-notation. do-notation allows you to create a mockup of an imperative, Turing machine-esq language within Haskell.

Let’s see the do-notation in action, alongside the code that the do-notation desugars to. We’ll write a simple progam that prints out the first 10 words in /usr/share/dict/words.

Original code: Desugared code:

main = do

wordList <- readFile "/usr/share/dict/words"

let words = take 10 (lines wordList)

putStrLn "Here are the first 10 words:"

mapM_ putStrLn words

main =

(readFile "/usr/share/dict/words") >>=

(\wordList ->

let

tenWords = take 10 (lines wordList)

in

(putStrLn "Here are the first 10 words:") >>

(mapM putStrLn tenWords))

And this, my friends, is a mathematically sound way to model sequential execution.

(If you’re interested, here is the documentation for what it means to be a Monad in the Haskell language).

Arrows #

Arrows are a way to encapsulate sequential actions as objects. It’s an idea borrowed from category theory, so we’re about to dive deep into trying to develop an intuition around these strange objects.

An “arrow” is a generalization of the idea of “monad” to the abstract realm of category theory. This first involves the question of “what is a category”?

As per Wikipedia, a category is “a labeled directed graph[…] whose nodes are called objects, and whose labelled directed edges are called arrows (or morphisms). A category has two basic properties: the ability to compose the arrows associatively, and the existence of an identity arrow for each object.”

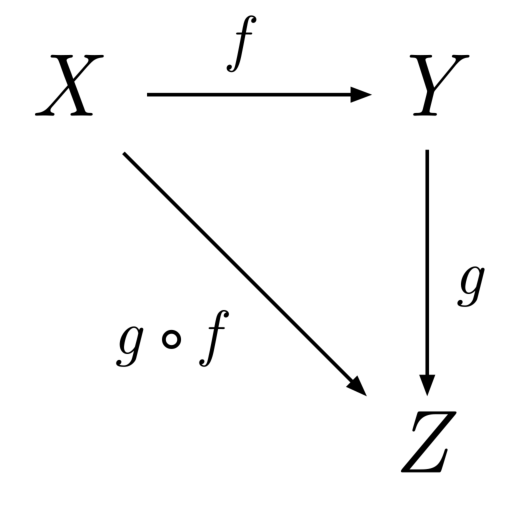

Here’s Wikipedia’s example of what a category looks like:

This category has 3 objects: \(\left \{ X, Y, Z \right \}\), and two explicit arrows: \(f : X \rightarrow Y, g : Y \rightarrow Z\). The composition of \(g \circ f\) has type \(X \rightarrow Z\). Every single object here has an implicit identity arrow connecting it to itself.

How would we represent a directional category graph like this in Haskell? Control.Category provides us with a way to represent a simple category with two objects and a single arrow between them.

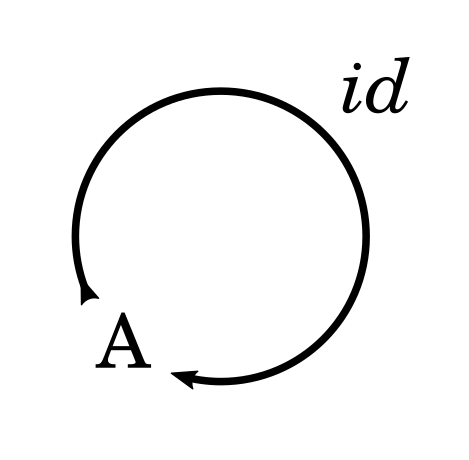

Let’s start with the simplest category, with one object \(A\) and a single arrow connecting \(A\) to itself. That would look like this:

We would represent this in Haskell as such:

import Control.Category

our_category = id

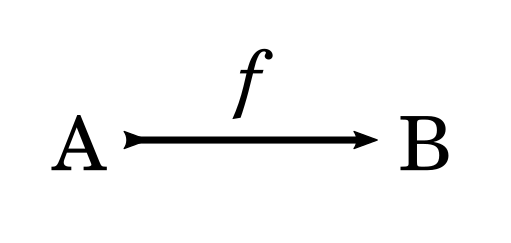

How about the simplest nontrivial category? We could represent it as a directed graph with objects \(\left \{ A, B\right \}\) and one arrow \(f : A \rightarrow B\). That would look like this:

Although, it will instead prove more natural to simply represent the arrows connecting the objects, as the Haskell type system already gives us a convenient way to represent objects as types. Thus categories we are constructing aren’t true categories per se, they instead exist in the space of Hask – every Haskell type. So, we only need to draw arrows between the objects of Hask to be able to construct our directed graphs,

(If we are going to be extremely formal with our language, we can say that we are working on a subgraph of the fully connected graph with objects \(o \in \text{Hask}\), where we are only interested in the objects \(\left \{ A, B \right \}\))

Enough of the formalisms, let’s draw these arrows using Control.Arrow.

import Control.Arrow

type A = ... -- it doesn't matter what we decide

type B = ... -- to make these two types, as long

-- as we can draw an arrow between them

f :: (Arrow a) => a A B

f = -- some implementation

We read the type of f as f is some arrow a from type A to type B. By default, two things in Haskell can automatically be coerced to arrows: pure functions, and monads.

Pure functions being coerced to arrows are rather boring. Let’s say that type A is the type of integers, and type B is the type of strings. We could then say that drawing an arrow f between A and B would be displaying an integer:

import Control.Arrow

f :: (Arrow a) => a Int String

f = arr (show) -- where `arr` lifts a function

-- to an arrow.

This is a useful abstraction to consider when you consider the composition of multiple arrows. But, before that, we’ll look at Kleisli arrows.

Despite sounding terrifying, Kleisli arrows are free instances of arrows that we can derive just because something is a monad. In other words, everything that is a monad is also by default an arrow. The reasons behind this are terrifying and hidden deep in the belly of category theory (tread lightly, if you dare), but the gist is that you can “pick out” arrows that are required as per the definition of a monad.

Now, we can dive into what this actually means for our computational purposes. Using this free arrow instance allows us to represent high level actions as cohesive objects under a Kleisli arrow a (the terminology “object” and “action” is used very loosely here).

Let’s use this to construct the same example as above: reading a words file and outputting the top 10 words.

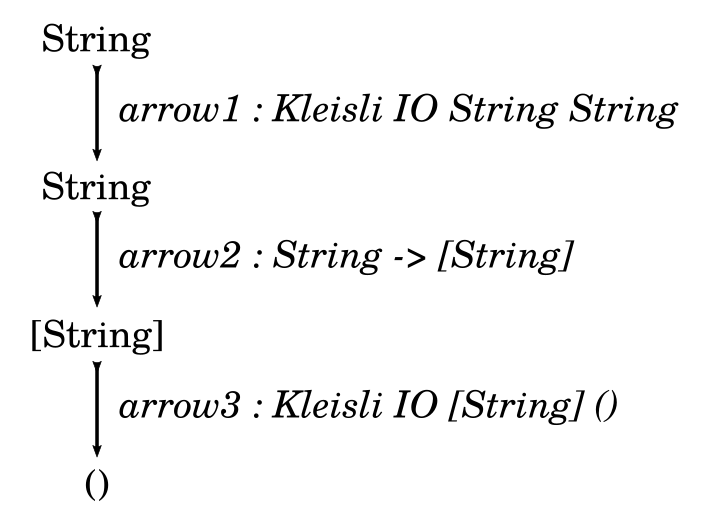

First, we make our imports and we define our first few arrows. We’ll make one arrow for reading a file, one arrow for turning the words into a list, and one arrow for printing the first 10 words of that list. Despite all my best intentions, I’ll call these arrows arrow1, arrow2, and arrow3 respectively.

import Control.Arrow

arrow1 :: Kleisli IO String String

arrow1 = Kleisli readFile

arrow2 :: Arrow a => a String [String]

arrow2 = arr lines

arrow3 :: Kleisli IO [String] ()

arrow3 = Kleisli (mapM_ putStrLn . take 10)

Then, to construct the category

all we need to do is compose our three arrows as

arrow1 >>> arrow2 >>> arrow3

which forms an arrow of type

(arrow1 >>> arrow2 >>> arrow3) :: Kleisli IO String ()

which can be run as

> (runKleisli (arrow1 >>> arrow2 >>> arrow3)) "/usr/share/dict/words"

A

A's

AMD

AMD's

AOL

AOL's

AWS

AWS's

Aachen

Aachen's

Note how it doesn’t matter that arrow2 took a String and not an IO String, even though it was being fed by a Kleisli arrow using the IO monad. This is because the Kleisli arrow fully encapsulates the fact that the String is in IO. If you’ve noticed earlier, our type signature for arrows was Arrow a => a A B. This type is parametrized over the type of the arrow as well as the types of A and B. In the case of our Kleisli arrow here, we let a be Kleisli IO, and thus the Kleisli arrow can encapsulate an IO action as a simple arrow.

And thus, we’ve established a higher generalization on top of the idea of the monad, and thus a second basis for sequential execution.

Arrows are super cool because of the many ways that you can combine them – and I didn’t touch on any of those ways in this blog post. If this was interesting, I urge you to read through and absorb the Haskell documentation for Control.Arrow, and mess around with it in your own copy of Haskell to develop some more intuitions about how these objects work.

What’s Next #

I was planning on writing about applicatives and other goodies (especially ArrowFix) down here, but this post is way too long already. Please send in your comments and clarifications using the contact info below! I love to hear from readers.