Good Symbolic Differentiation Requires Multidimensional Wobbliness

Over the past couple of days, I’ve been working on a Haskell script to do symbolic differentiation. Despite the fact that I’m more than a few semesters into a math degree, I’ve learned a ton while working on this little project. Differentiation can be a harder problem than it seems – especially when we’ve been trained to trust our intuition about things.

To represent symbolic mathematics, I’ve created a moderately sized inductive data structure. This should be familiar to anyone who’s used Haskell before, and fairly easy to figure out otherwise:

data Op =

Plus Op Op

| Mul Op Op

| Pow Op Op

| Ln Op

| E Op

| Pi Op

| Const Rational

| Var

This structure can store simple expressions in forms such as \(2 + 2 \Leftrightarrow Plus\;(Const\;2)\;(Const\;2)\)

It only supports holding one variable at a time, using the Var constructor. This means that every single expression that Op can hold only depends on one variable, which I’ll refer to as \(x\) through the rest of this post.

Then, to take the derivative of the expression stored in this data structure, we use the function d. d is defined inductively on the Op datatype. For simple cases, this is easy. For example, the derivative of a constant is always 0, and the derivative of a bare variable is always 1.

d (Const u) = Const 0

d (Var) = Const 1

We can get all the easy cases out of the way relatively quickly. Let’s continue – the derivative of \(u(x) + v(x)\) is \(u’(x) + v’(x)\):

d (Plus u v) = Plus (d u) (d v)

And now we’ll break out the product rule: the derivative of \(u(x)v(x)\) is \(u(x)v'(x) + u'(x)v(x)\):

d (Mul u v) = Plus (Mul u (d v)) (Mul (d u) v)

Taking the derivatives of \(e^{u(x)}\) and \(\pi^{u(x)}\) get us \(u’(x)e^{u(x)}\) and \(u’(x)(\ln{\pi})\pi^{u(x)}\) respectively

d (E u) = Mul (d u) (E u)

d (Pi u) = Mul (d u) (Mul (Pi u) (Ln (Pi (Const 1))))

Finally, taking the derivative of \(u(x)^{v(x)}\) is—

well, more difficult.

Deriving A Mistake #

By how I wrote it above, \(u(x)^{v(x)}\), I’m already giving away some of the solution. For the sake of guiding you, the reader, through the rabbit hole of my thought processes, I’m going to refrain from uniformly referring to \(u\) and \(v\) as functions until the “big reveal” at the end of this section.

Do note that I’m writing this up primarily to show how I corrected my incorrect judgements, so I will try very hard to explicitly highlight the errors in the ideas presented.

My first thought was to try the classical chain rule \(\frac{d}{dx}\left(f(g(x))\right) = f’(g(x))g’(x)\). That’s the one that everyone learns in Calculus 1, and it’s what lead me through so much faulty intuition.

I started by splitting up this exponential into two parts. For consistency with the definition above, I will call these two parts \(f(v) = x^{v}\) and the exponent \(v(x)\). Astute readers will already see plenty wrong with my initial judgement.

Yet alas, along I trekked. Using these formulas for normal exponentials seemed to work fine. Take the derivation of \(2^{3x}\) for example.

\[\frac{d(2^{3x})}{dx} \\ =\frac{d(2^v)}{dv}\cdot\frac{d(3x)}{dx}\\ =(\ln{2})(2^{3x})\cdot3\]

This was indeed the correct answer.

My intuition broke down while trying to consider exponentials in which the base was not constant. Even the simplest case, \(x^2\), would fail. According to this rule:

\[\frac{d(x^2)}{dx}\\ =\frac{d(x^v)}{dv}\cdot\frac{d(2)}{dx}\\ =(\ln{x})(x^2)\cdot0\\ =0\]

Of course, this isn’t the correct answer in the slightest.

The error lies in how I had defined the function \(f(v) = x^v\). By how it was written, \(f\) only depends on \(v\), not \(x\). Thus, for all intents and purposes, \(f\) treats \(x\) as a constant parameter, instead of the ever changing variable that we had wanted.

In the case that \(x\) really was supposed to be constant, this still wouldn’t have been the correct solution: \(\frac{d(2)}{dx}\) would have been indeterminant since \(dx\) would have been nonsensical and/or uniformly zero.

When writing it out afterwards, it seems so obvious — but at the time, I’d gotten so frustruated with this that I was convinced that my last three years of math education were all wrong.

With new intuition on our side, it should be expected that the actual algorithmical method to find this derivative will be multiple terms, since the derivative of the exponent \(2\) will always cause some term to multiply out to zero.

Into The Next Dimension #

After a long flame war in the Mathematics discord, with every (correct) way of finding \(\frac{d}{dx}(u(x)^{v(x)})\) being touted as The Only Way To Do It, someone had suggested using the multivariate chain rule instead.

For those who have yet to take Calculus III, the multivariate chain rule is a generalization of the chain rule for functions with an arbitrary number of arguments. To utilize it, we must take our original expression \(u(x)^{v(x)}\) and manipulate it into the definition of some higher order function \(f\):

\[f(u:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R},v:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}) = u(x)^{v(x)}\]

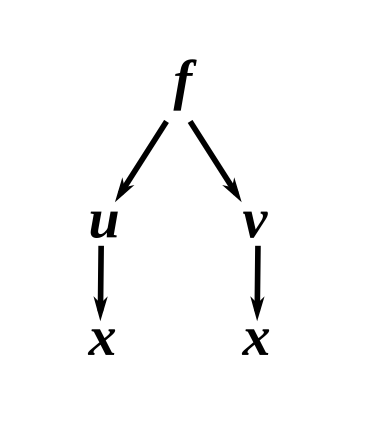

Next, we will draw a dependency graph to see what functions depend on the values of what variables.

This can be read as “the function \(f\) depends on two functions, \(u\) and \(v\). The function \(u\) depends on the variable \(x\). The function \(v\) depends on the variable \(x\)”.

To find \(\frac{df}{dx}\), we must traverse this graph in its entirety. \(f\) depends on \(u\) and only \(u\); \(x\) does not exist in the context of \(f\). Thus, the derivative of the first branch of the graph is \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\).

We aren’t interested in change with respect to \(u\) though, we are interested in change with respect to \(x\). To find this, we must multiply \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\) by the change of \(u\) with respect to \(x\):

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\frac{du}{dx}\]

This is only half of the total derivative of \(f\). The entire total derivative of \(f\) is actually the sum of all of its partial derivatives. In other words:

\[\frac{df}{dx} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\frac{du}{dx} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial v}\frac{dv}{dx}\]

As simple as that, we have an algorithmic method for determining the derivative of \(u(x)^{v(x)}\)

Putting It To The Test #

Let’s try the example from earlier, \(\frac{d(x^2)}{dx}\).

First, we’ll define our functions.

\[f(u,v)=u^v\\ u(x)=x\\ v(x)=2\]

Next, we’ll find our derivatives.

\[\frac{\partial f}{\partial u} = vu^{v-1} \\ \frac{du}{dx} = 1 \\ \frac{\partial f}{\partial v} = u^v\ln{u} \\ \frac{dv}{dx} = 0\]

Do note that as long as our \(f\) is of the form \(u^v\), neither of the partial derivatives will change. This is important for later when we bring this algorithm back to the code.

Substituting all these derivatives into \(\frac{df}{dx} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial u}\frac{du}{dx} + \frac{\partial f}{\partial v}\frac{dv}{dx}\) gets us:

\[\frac{df}{dx} = vu^{v-1}\cdot1 +u^v\ln{u}\cdot0\]

Plugging in our values for \(v\) and \(u\) and simplifying gives us:

\[\frac{df}{dx} = 2x\]

Perfect! (Further examples left as an exercise for the reader!)

Back To The Future #

Finally, we can write the code for deriving arbitrary powers:

d (Pow u v) = Plus (Mul df_du du_dx) (Mul df_dv dv_dx)

where

df_du = Mul v (Pow u (Plus v (Const $ -1)))

du_dx = d u

df_dv = Mul (Pow u v) (Ln u)

dv_dx = d v

And see it in action:

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( taylor.hs, interpreted )

Ok, one module loaded.

*Main> Pow (Var) (Const 2)

x^{2.0}

*Main> d (Pow (Var) (Const 2))

(((2.0*x^{(2.0+-1.0)})*1.0)+((x^{2.0}*ln[x])*0.0))

*Main> fullSimplify $ d (Pow (Var) (Const 2))

(2.0*x)

*Main> fullSimplify $ d (Pow (Const 2) (Var))

(2.0^{x}*ln[2.0])

Stay tuned to see what I have planned for this code!

Thanks to the Mathematics Discord server for talking through this with me. Join the conversation here: https://discord.sg/math/.

More #

Gitcommit sent me a few resources to look at if this article interested you. They’re very good, and I highly recommend reading through these if you want to see a few different approaches to differentiating formulas programatically:

Dual Numbers and Differentiation by Gitcommit.

What is automatic differentiation, and why does it work? by Conal Elliott.

Learn Physics by Programming in Haskell by Scott N. Walck.