Raku is the World's Worst ML (with addendum by Damian Conway)

While reading through the docs for Raku’s multi-dispatch, I noticed something familiar: the language chooses which multi function to call depending on which routine’s signature matches the argument first. Since Raku uses the smartmatch operator ~~ to match up type signatures, that means that we can also match on arguments by value….

10 minutes later, and I’ve created this abomination:

proto len(@ --> Int) {*}

multi len([] --> 0) { }

multi len(@ [$, *@rest] --> Int) { 1 + samewith(@rest) }

say len <1 2 3 4 5 10>; # => 6

… equivalent to the much more readable Haskell version…

len :: [a] -> Integer

len [] = 0

len (_:rest) = 1 + len rest

main = print $ len [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10] -- => 6

The Raku code uses a few fun tricks that I’d like to point out.

The proto declaration is entirely optional, just as the type signature in the Haskell version is entirely optional. I left them both in beacuse it’s fun to compare the two versions.

The first multi declaration has the signature ([] --> 0). Therefore, this branch of the len routine is only called when the argument smartmatches against []. When that smartmatch succeeds (when the argument is empty), --> bypasses the body of the function and instead returns a constant value (behavior documented here).

The second multi declaration has the signature (@ [$, *@rest] --> Int). The first half of this signature pattern matches on a nonempty list: @ is the positional sigil, which we leave anonymous since we don’t need to use its value. [$, *@rest] is where the list deconstruction actually happens – it matches against a single head value $ which we leave anonymous, and slurps up the rest of the list into @rest.

Finally, the 1 + samewith(@rest) line recurses through the list. samewith (documented here) calls len with a new argument and the process repeats all over again, all the way down until we hit the base case.

No ML would be complete without some sort of abstract data type. Fortunately, we can emulate ADTs using classes and parametrized roles. Let’s start by defining our Maybe ADT (reference for the uninitiated).

role Maybe[::A] { }

sub just(::A $x --> Maybe[::A]) { class Just does Maybe[::A] { has $.V = $x; }.new }

sub nothing(Any:U $t --> Maybe[$t]) { class Nothing does Maybe[$t] { }.new }

Here, we define Maybe as a parametric role. We define the constructors just and nothing as routines that return parametrized classes Just and Nothing respectively. Unfortunately, because Raku lacks any sort of meaningful type inference, the constructor for Nothing still needs to take in the uninhabited type which it will unify with as an argument.

Now, we can pattern match on the classes produced by our constructors to interact with our Maybe values.

my @maybes = just(1), just(2), nothing(Int), just(4), nothing(Int);

proto print-maybe(Maybe $) {*}

multi print-maybe(Just $m) { $m.V.say }

multi print-maybe(Nothing $) { 'nothing'.say }

@maybes.map: { print-maybe $_ }

This produces:

1

2

nothing

4

nothing

And finally, compare this to the equivalent Haskell code:

print_maybe :: Show a => Maybe a -> IO ()

print_maybe (Just m) = print m

print_maybe (Nothing) = putStrLn "nothing"

Sorry. Hope you enjoyed this :)

If this piqued your interest, check out the Haskell to Raku page of the docs, or download Raku and give it a try for yourself.

Addendum (updated July 6th, 2019) #

Here’s Damian Conway, a Raku language designer, on the goals of the Raku language in relation to this post:

One of the original Raku design philosophies was that complexity is intrinsically irreducible…but extrinsically redistributable. See: “The waterbed theory of language design”.

In line with that belief, Raku almost always attempts to redistribute its syntactic complexity towards declarations…and away from calls. Mainly because declarations are typically written once, by a small number of expert developers, whereas calls are typically written many times, by a large herd of shall-we-say-less-than-expert developers.

In other words, Perl tries to put the complexity where it will do the least harm, and where its victims may have the best chance of surviving it. :-)

[snip]

Of course, I’m not claiming that this high degree of flexibility is an unalloyed benefit (because there are plenty of plausible syntactic variations that wouldn’t Do The Right Thing so obligingly). But in all those cases, the resulting error message is guaranteed to be clear and helpful, because any Raku error message that is LTA (“Less Than Awesome”) is officially considered to be a bug!

The forgiving nature of Raku syntax reflects several more of its fundamental design principles:

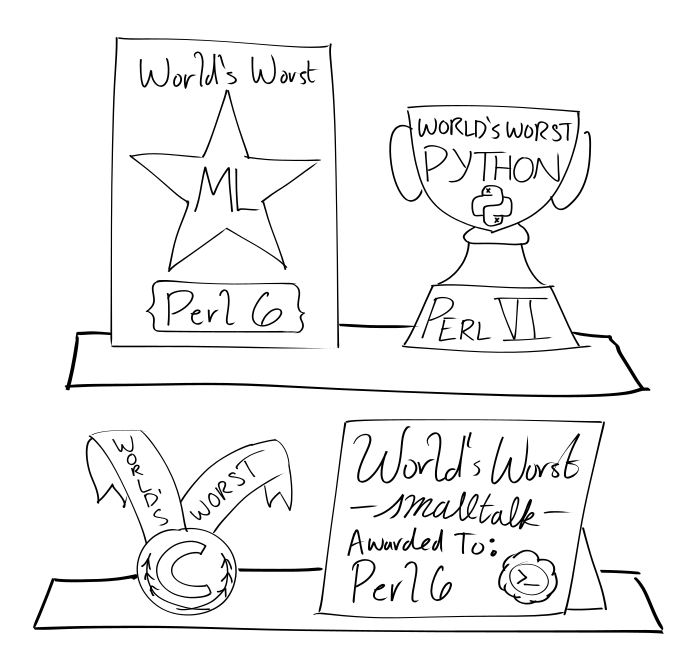

* Raku tries to do what you meant, not merely what your said. * Raku has a long--but gentle--learning curve. * It's perfectly okay to write "baby Perl". * There's far more than one way to do it.Ultimately, I think that we’re pretty happy with Raku being the “World’s Worst ML”, so long as it can also (simultaneously) be: the “World’s Worst Smalltalk”, the “World’s Worst Lisp”, the “World’s Worst Snobol”, the “World’s Worst QCL”, the “World’s Worst Erlang”, the “World’s Worst Prolog”, the “World’s Worst Python”, the “World’s Worst C”, and even the “World’s Worst Perl 5”.

Because that was one of our design goals too. :-)

He also offers this alternate, more readable definition of len:

proto len(Positional --> Int) {*}

multi len ([]) { 0 }

multi len ([$, *@rest]) { 1 + len @rest }

say len <1 2 3 4 5 10>;

# or say len [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10];

# or say len (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10);

# or say len 1...5, 10;

# or List.new(1,2,3,4,5,10).&len.say;

and argues that this is all just as readable (if not more) than the Haskell version. I’m inclined to agree.

I responded:

Thank you & all the Raku design team for making such a fascinating language :)

Sorry for the inflammatory blog title, but there’s no way to get clicks better than throwing around big words like “world’s worst” – even if later revealed that it was meant as a form of praise. I’m truly impressed that Raku can emulate the semantics of an ML-like language so closely. I didn’t even touch on

whereblocks in the post because I couldn’t think of any fun examples, but that just drives the point home even more.Let me respond to a few points you brought up in your reply:

I have some strong opinions about actual badly designed MLs, but that’s another conversation entirely :^)

I definitely didn’t completely intend to write such an abomination of a Raku example for the

lenfunction, haha. The post was written in jest at the fact that I wrote code that I thought was so obviously un-Perl-esq – but it blows my mind that with a few little readability changes it turns into code that’s quite readable and pragmatic. I’ve only been writing Raku for something along the lines of four days, so I appreciate the cleaner code examples (I might’ve gotten a little bit carried away with abusing the-->operator. And usingPositionalinstead@is much cleaner as well, thank you).Raku almost always attempts to redistribute its syntactic complexity towards declarations…and away from calls.

- This makes a lot of sense – I’ve noticed a lot of things in Raku that are “deceptively simple”. It’s very well designed in that aspect; for example, an ordinary user never has to worry about how a Signature is matched against its arguments, whereas a power user has the opportunity to manually interact with Signatures, Captures, and the like. It doesn’t feel like “complexity” is the right word to use for this behavior, since it’s all largely contained in a way that you’ll never have to fiddle with it on a normal day. Given/when (or react/whenever) blocks are another example of this sort of well designed contained complexity in my opinion. In a normal use case, the programmer never has to worry about what

givenactually does, or howwhenevermatches against what comes out of a supply; but the option is always there to delve deeper.The forgiving nature of Raku syntax reflects several more of its fundamental design principles:

- Where are the design principals located? That sounds like an interesting thing to write about on its own.

Ultimately, I think that we’re pretty happy with Raku being the….

- Between the ability to define expressive grammars, implement custom operator syntax, write macros, etc, it feels like you could emulate most any paradigm you’d desire inside of Raku. In a previous blog post I wrote (https://aearnus.github.io/2018/07/09/programming-language-diversity), I talked about how I felt like that flexibility was key to a language surviving and thriving.

His response:

I might’ve gotten a little bit carried away with abusing the

-->operator.Not at all. That’s exactly why we put it there: so that people who think the way you do can write code the way they prefer. Whereas people who think like C programmers can write:

my Int sub len (@list) { return @list ?? 1 + len(@list[1..*]) !! 0 }Bless their hearts.

- Where are the design principals located?

Mostly in Larry Wall’s brain. And mine.

Initially they were promulgated in Larry’s original design documents:

https://perl6.org/archive/doc/apocalypse.htmland elaborated in my commentaries:

https://perl6.org/archive/doc/exegesis.htmlThough both of those are now hopelessly out-of-date.

Larry and I have each given talks about various subsets of those principles, some of which are available online (either as videos or as summary documents):

https://www.infoq.com/presentations/language-design-perl http://www.wall.org/~larry/natural.html https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8xXrhjqOZM https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JzIWdJVP-wo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJIfPFpaMRI

- Between the ability to define expressive grammars, implement custom operator syntax, write macros, etc, it feels like you could emulate most any paradigm you’d desire inside of Raku.

That’s certainly our goal: a language that lets you solve problems the way you solve problems.

I have a class called “Transparadigm Raku” where I show the same solution in a wide range of different paradigms (and in a range of intermixed hybrid paradigms - hence “transparadigm”)…all in Raku.

For example:

{ # Median value (imperative)... sub median (*@list) { @list .= sort; if @list.elems %% 2 { return 0.5 * [+] @list[*/2, */2-1]; } else { return @list[*/2]; } } say median(2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19); } { # Median value (functional)... sub median (*@list) { given @list.sort { .elems %% 2 ?? 0.5 * [+] .[*/2, */2-1] !! .[*/2] } } say median(2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19); } { # Median value (hybrid imperative/functional)... sub median (*@list) { my @sorted = @list.sort; return @sorted.elems %% 2 ?? 0.5 * [+] @sorted[*/2, */2-1] !! @sorted[*/2] } say median(2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19); } { # Median value (declarative functional)... sub median (*@list) { sub sorted { @list.sort } return sorted.elems %% 2 ?? 0.5 * [+] sorted.[*/2, */2-1] !! sorted.[*/2] } say median(2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19); } { # Median value (hybrid OO/declarative functional)... class StatList is List { method median () { sub sorted { self.sort } return sorted.elems %% 2 ?? 0.5 * [+] sorted.[*/2, */2-1] !! sorted.[*/2] } } StatList.new(2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19).median().say; } { # Median value (method added directly to the built-in List type)... use MONKEY-TYPING; # i.e. I am about to do something mischievous augment class List { method median () { sub sorted { self.sort } return sorted.elems %% 2 ?? 0.5 * [+] sorted.[*/2, */2-1] !! sorted.[*/2] } } say (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19).median(); }I’m a big believer in languages adapting to the needs of the speaker, not vice versa. Just as there’s no one right way to speak in English, there should be no one right way to code in your preferred programming language. Most languages don’t really support that notion; many of them, in fact, are based on the diametrically opposite principle: “Everything has to be pure functional”, “Everything has to be objects”, “Everything has to be declared relationships”, “Everything has to be independent unreliable intercommunicating threads”. Each of which, in my opinion, is equivalent to: “Here’s your one true hammer. Now everything has to be a nail.”

Which, of course, serious developers reject. That means they now have to be fluent in Haskell and Erlang and Python and Node.js and a dozen other completely distinct and mutually incomprehensible development tools. And they have to continually context switch between them when writing and debugging and maintaining. And the vast majority of us just aren’t good at that.

That’s why I devoted two decades of my life to helping ensure that Raku lets you solve problems in whatever (reasonable) way that suits you…and suits your problem! By all means solve the majority of your problem functionally, but implement the inherently stateful parts of your program with objects, and handle the intrinsically linguistic components with declarative grammars. But do it all in the same language and at whatever granularity you are most comfortable with.

It’s not for everyone, of course, but it makes me happy. :-)

Comments? Improvements? Ideas? Contact me below.