Writing a rootkit, by someone who knows nothing about computer security

For some God awful reason, my most popular repo on Github is syscall-rootkit. It’s a tiny Linux kernel module that intercepts syscalls to read(2) and write(2). As of writing this blog post, it has 11 stars and 8 forks. Fingers crossed that those 8 people are using the code for good.

As far as how the program works, it’s actually very simple. Once compiled, it can be hot loaded into the kernel as a kernel module (using insmod) and it replaces the pointers of read(2) and write(2) with pointers to its own rk_read and rk_write functions. The code is short and sweet enough to fit on one page.

This simplicity didn’t come easily. It came after struggling quite a while with some nasty gotcha’s…

KASLR #

(or, why this isn’t actually a rootkit).

Typically, from the information I’ve gathered browsing Wikipedia and watching Youtube, a rootkit has a few very important properties:

-

It buries itself deep into the innards of a system.

-

It persists across boots and removal attempts.

-

It makes a reasonable attempt to hide itself from the end user.

-

It installs itself surreptitiously.

Now, uhm, let’s look at which of these syscall-rootkit manages:

-

✔️ It buries itself deep into the innards of a system.

-

❌ It persists across boots and removal attempts. 6/22/18: EDIT: ✔️

-

❌ It makes a reasonable attempt to hide itself from the end user.

-

❌ It installs itself surreptitiously.

So, calling this project a rootkit in the first place is optimistic at best.

Points 3 and 4 are really only of concern for people who want to do harm, and I’m not really here to hurt anybody. So, throw those out the window and only focus on points 1 and 2. We’ve got point 1 down pat: I’m not sure any program could get lower and deeper than the kernel without getting into any funny business.

Last, but not least, we come to point 2. As a random guy and not a security researcher, the concept of a program trying to evade and block removal attempts is…

That leaves the final point to talk about. The first part of point 2 points out the fact that the rootkit must “persist across boots”. This is an issue because of KASLR. Kernel Adress Space Layout Randomization a security measure implemented in the Linux kernel which ensures that every important bit of data and every table in the kernel’s memory is placed at a random spot at every boot-up. This is to prevent idiots like me from overwriting the syscall table. KASLR is generally not a very large impediment to a black hat who’s sufficiently dedicated to causing harm, with the Google search for “bypass Linux KASLR” returning 18,300 results

and a Google search for “bypass Windows KASLR” revealing a writeup on a longstanding Windows NT bug to bypass KASLR up until Windows 8.1.

Because of the fact that the point of my project wasn’t to exploit KASLR (and out of laziness), I took a little bit of an easier approach to all of this.

6/22/18: EDIT: Everything between this line and the next notice is wrong, but I’m keeping it for posterity/correctness/to laugh at later. I was under the impression that System.map accounted for KASLR; when in reality, the last time I had tested the rootkit was before KASLR was enabled by default in Linux, and that’s why it worked in the first place. Just some proof that I really am writing and learning at the same time.

This approach, though, doesn’t allow the “rootkit” to persist across boot-ups. Enter make.rb.

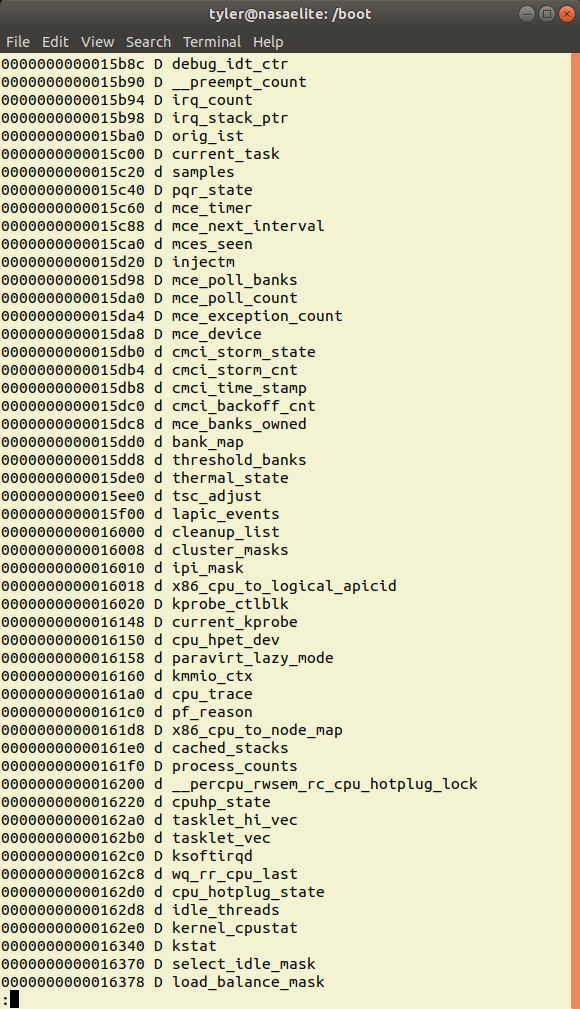

This hack of a script uses a templating engine to bake the address of the KASLR-hardened syscall table right into the code itself. To find this address, the script accesses a read-only file system exposed by the Linux kernel at /boot/. In /boot/, there exist System.map files which contain the absolute offsets of every single symbol in the kernel address space for that session (or possibly for that version of the kernel? I’m not too sure, actually).

A screencap of the a bit of my System.map file, near the top.

It just so happens that the table that stores all the Linux system calls is also listed in the System.map file.

linuxVersion = `uname -r`.chomp

puts "uname -r = #{linuxVersion}"

puts "using /boot/System.map-#{linuxVersion}"

syscallOffset = `sudo cat /boot/System.map-#{linuxVersion} | grep ' sys_call_table' | ruby -ane 'print $_.split(" ")[0]'```

This little block of Ruby code serves two purposes. The first purpose is to prove that anything can work with enough hacked together duct tape. The second purpose is to store the offset for the syscall table (labelled `sys_call_table`) in a variable `syscallOffset`. Once this variable is populated, it's placed in a string which is then templated to the top of the main C file for the rootkit.

```ruby

define = "#define SYS_CALL_TABLE ((unsigned long**)0x#{syscallOffset})"

SYS_CALL_TABLE is then used throughout the code to reference the table that holds the Linux system calls. Take that, KASLR!

On the next reboot and/or on the next update of the kernel, the address of that table will change and thus the rootkit will stop working (along with the rest of your computer, most likely).

6/22/18: EDIT: Here’s the correct version that actually accounts for KASLR

Oops. So upon testing the previous method, I couldn’t manage to make it do anything but kernel panic. Turns out, the System.map file doesn’t accurately represent the kernel address space. Instead, KASLR shifts the kernel’s address space listed in System.map by a random constant. This has been the case since it was turned on by default in Linux 4.12.

This prompted me to stop using the overcomplicated hack that was the make.rb file. Instead, in the process of making this edit, I came across the kallsyms_lookup_name function (I wasn’t kidding when I said I didn’t know what I was doing). From linux/kallsyms.h, this function allows you to look up a dynamic kernel space symbol by its name on-the-fly. With this solution working (and working much better than my previous solution 😛), I’m happy to give myself that check mark for point 2.

With this new method, I could also retire the superglue that is make.rb, allowing this rootkit to be built from just a Makefile alone.

Here’s the one drawback about resolving the syscall table address this way: kallsyms_lookup_name is part of a GPL licensed API, meaning I am legally required to release this rootkit as GPL. It’s now as free as freedom can get.

The CR0 byte #

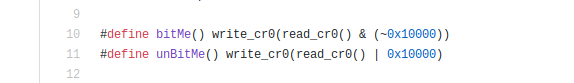

Notice this? These two lines gave me more headache than the rest of the code combined. Here’s the kicker: without running these two macros, the entirety of the kernel module does absolutely nothing, with no indication that anything even went wrong. There’s no compile time error, there’s no segfault, and the CPU doesn’t throw. Read on to find out why…

Code from hell.

❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗

If you ever, and I mean ever see this in an actual kernel module, run screaming in the other direction. Run as far away as you possibly can. This is a massive security risk and the product of a programmer who has absolutely no idea what they are doing or the power that kernel level code wields. If you’re going to scold me for writing this, I beg that you save your breath. I already know, and I’ve handled it as safe as I possibly could. Which, to be fair, isn’t very safely.

❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗❗

Anyway.

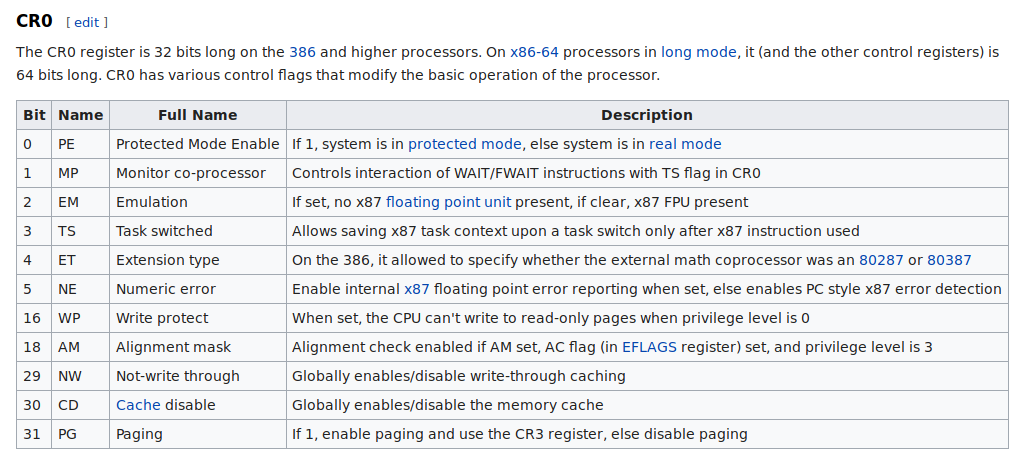

CR0 is a x86 specific Control Register used to control various properties of an x86 CPU. The write_cr0 and read_cr0 macros are defined in asm/paravirt.h and do exactly what they say on the tin: write to and read from the CR0 register. CR0 controls quite a few things about the CPU.

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Control_register#CR0.

Those little macros above switch on and off bit 16 (0x10000 is equivalent to 0b10000000000000000 – everything turned off except the 16th bit). CR0’s 16th bit is write protection. That macro disables ring 0 write protection, meaning everything that shouldn’t ever change in kernel space suddenly becomes free game. It’s taking every single modern security feature and chucking it straight back to the 60’s, with all of its peeks, pokes, and unprotected memory. It’s like waving a magnet over your RAM and expecting everything to be perfectly fine afterwards. So, I’m careful to only modify what I need before turning that write protection right back on.

Those modifications are right here. All I do is save the original read(2) and write(2) calls into their own respective original_ functions (which really should be done before flipping the bit on CR0). Then, I replace those slots in the SYS_CALL_TABLE with my own function pointers and flip the bits on CR0 right back to how they should be. That’s all there is to it. After doing that, I have full control over the system calls I overwrote – and even more so, I have full control over any arbitrary kernel function (should I choose to modify it).

Seeing It All Come Together #

Here’s where I would put cool screenshots of the rootkit fishing out every sudo password you typed in and intercepting every single time a program wrote to a file. But, to be honest, I have a real moral obligation not to do that.

Just kidding.

It’s not the moral obligation that stopped me. It’s the fact that no matter what I tried, I couldn’t get anything to not hang the entire machine. Here’s my best attempt at code that logged every call to read(2). Payloads are hard, man.

Final Words #

If I had one takeaway from this whole process, it’s that full control doesn’t come easily. Building and installing this module requires superuser access for two separate commands 6/22/18: EDIT: One command now, but that’s still non-negligible., and for many Linux users, that’s too important to take with a grain of salt. Figuring out a way to place that on a computer without them knowing would require a real feat of social engineering (or a real bad privilege escalation exploit). Even more so, kernel modules don’t have access to the same set of C functions that userland applications do, so doing anything non-trivial is another feat of engineering in and of itself. All in all, this was a hell of a lot of fun to build, and a great learning experience. I’d just hope that those

syscall-rootkit aren’t any more evil than I am 😄.

If you like what I do, please support me on Liberapay or Patreon!